Katelyn Beaty

Harvard for Homeschoolers?

A gallery of photos from Patrick Henry College.When did conservative Christians become odd, fascinating creatures to bring under the journalistic lens? The friendly poking and prodding predated God's Harvard (Harcourt, 2007), religion writer Hanna Rosin's dispatch from an 18-month visit to Patrick Henry College, but her account certainly exemplifies the genre. Admitting upfront that she is "democratic almost to a fault," Rosin spent much of that book trying to cast a humanizing light on conservative Christian youth at the "Harvard for Homeschoolers" in Purcellville, Virginia. Yes, they were sheltered, perfectionist, naïve about the things normal college students indulge in, and driven, to Rosin's dismay, to "take back the nation" via political and cultural power. Yet they also were becoming open to the world beyond homeschooling life, and were starting to question their inherited model for living out faith in the world. In the students she befriended, Rosin saw an embodiment of evangelicals' move into the American mainstream—or, as the cover of Christianity Today's golden anniversary issue put it in 2006, their journey from "cultural curiosities to the new internationalists."

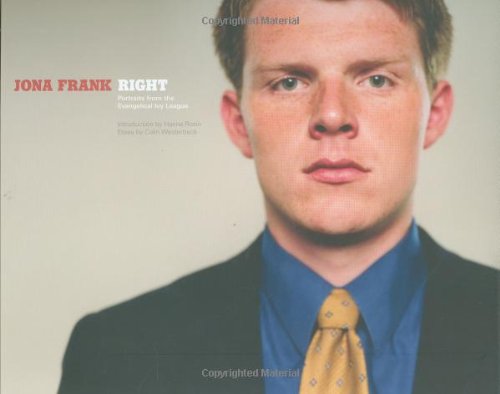

If God's Harvard was a portrait of Patrick Henry in words, then Jona Frank's Right: Portraits from the Evangelical Ivy League—published last fall, when the presidential election campaign was still in full swing—should serve as a companion volume, a portrait in, well, portraits. A West Coast photographer interested in American adolescence, Frank learned of Patrick Henry from Rosin's 2005 coverage in The New Yorker. Frank intended to visit the school for a project about teenage boys, but quickly became intrigued by PHC at large. "I felt like I had walked into a strange time warp," writes Frank in the book's postscript. "The first generation of homeschoolers was coming of age, and I was awash with curiosity."

That curiosity resulted in a sleek collection of Frank's photographs—mostly of students, but also of their many-membered families, and of paper documents that Frank apparently thought necessary to include for us to grasp Patrick Henry. Among these documents is a homeschooled child's glowing review of a George W. Bush biography; the school's honor code proposal, which includes vows to abstain from alcohol and to seek parental guidance when pursuing romantic relationships; and a page from Home School Digest instructing girls how to be helpmeets who are "willing to give up all your dreams" upon marriage. Frank's choice to include this last piece is a little irritating, especially as it's placed alongside a picture of an ecstatic young woman huddled with friends in a candlelight ceremony for newly engaged students. It's true: we can't understand how Patrick Henry students, including this young woman, think of matrimony apart from the prescriptions given in childhood. But Frank's juxtaposition suggests a direct pipeline from idea to person—that these students are no more than conduits of a way of living Frank clearly finds "other." In her introduction to Right, Hanna Rosin writes, "Jona's gift is to be able to see … the common uniform of the school, without resorting to cliché or judgment." Yes, Frank does seem more charitable toward her subject matter than many previous onlookers. It's hard to tell, though, if these documents are intended to help us more fully understand, or to keep Frank's subjects at arm's length—to emphasize that they are nothing like you and me.

Still, Frank is foremost a photographer, and she lets most of the images in Right speak for themselves. Her subjects look head-on at the camera with an earnestness that conveys concerns far beyond college life. Most Patrick Henry students wear ties or pantsuits and appear ever-prepared for work, though not without some nervousness about being center stage. Frank places her subjects in surroundings that most clearly reflect their identity: in the classroom, at home with parents and siblings, next to a painting of the founding fathers, on the campus lawn with a romantic interest. This is meant to depict Patrick Henry students as they really are, in their natural habitats. The lighting of the portraits suggests a stance of cool objectivity.

But while Frank's style is candid and almost harsh, she doesn't pretend to have the omniscient view of reality that much documentary photography of the early 20th century did. Right is not a hard-hitting investigation into conservative Christian youth with political aspirations, but rather an introduction to a religious community with cultural particularities often outside the American mainstream. In Right's final essay, curator and UCLA professor Colin Westerbeck identifies Frank as an artistic heir of Irving Penn, the celebrated portraitist. "Frank isn't a news photographer," he observes. "Like Penn's portraits of public figures, Frank's of the students at Patrick Henry College give you not just a chance to see her subjects, but a way to think about them."

So, what are the ways Frank wants us to think about these students? In her other book of photography, High School (Arenas Street, 2004), Frank captured teenagers trying on personas borrowed from MTV and advertising. "I am captivated with states of becoming," Frank writes, "and I am driven to make portraits of people as they … struggle with the pivotal moment between exploration and discovery." Frank's interest in metamorphosis emerges in Right as well: in the portrait of Taylor, a stubble-chinned young man wearing an oversized suit and confident gaze (p. 19); of Juli, proudly standing beside a portrait of George Washington on one page, and on another, patiently sitting with her siblings as their mom reads aloud from the Chronicles of Narnia (pp. 43, 51); and of Sherri and Paul, a couple who in one set revel in goofy traditions for the newly engaged, and in another, stand before a large cross as they make audacious commitments to fidelity and lifelong support that are more "adult" than some married adults can handle. These students are at once children and grownups, but not fully either.

Both Frank and Rosin are quick to find in this tertium quid a fable for politically conservative Christians' journey from backwoods to big time (and maybe back to the woods, as talk of "the death of the Religious Right" has been revived in the Obama era). They are correct to see in Patrick Henry an explicitly political mission. The college's founder, Home School Legal Defense Association president Michael Farris, sees Patrick Henry's students as members of "the Joshua Generation," who will "take back the land" from secular humanists and corrupt politicians by reaching positions of influence. Many PHC students study government and go on to intern with Republican congressmen or volunteer at the White House. (According to Anthony Buncombe's 2004 profile in The New Zealand Herald, only one student had interned with a Democrat.) A couple of students Frank interviewed told her of being treated to pizza and sundaes at Attorney General John Ashcroft's home. It's no wonder reporters have invented an array of uncharitable nicknames for the students, and are quick to link them to Chancellor Farris's less-than-PC statements on church and state.

But behind all this scary, ire-raising talk are the very students whom Frank and Rosin seemingly took pains to profile with even-handedness and grace. "The great thing about photography: It describes," reads Frank's postscript. "It allows us to glimpse a world different from our own. It brings us in and lets us think and wonder." As a member of the evangelical community who would likely feel bothered at Patrick Henry, I nonetheless wish Frank had let us think and wonder about the school a bit more freely. I wish she had let her camera attest to the persistent failure of persons and communities to fall neatly into the demarcations we employ to try and grasp the messy reality of American life.

Katelyn Beaty is associate editor with Christianity Today magazine.

Copyright © 2009 by the author or Christianity Today/Books & Culture magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Books & Culture.

No comments

See all comments

*